by Jordon Ferber

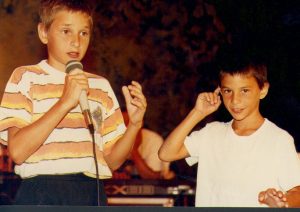

In July 2002, I was just two years into my burgoning stand-up comedy career when my only brother Russell, who was just about to embark on his own career as a pastry chef, was killed in a car accident. He was 21.

Just hours after his death, my dad asked me what kind of funeral he would have wanted. I told him I had no idea. I just knew the cake afterwards had better be amazing. And chocolate.

That’s the thing about the immediate aftermath of grief. You find yourself having surreal conversations about things like cake in the context of one of the most devastating moments one can experience.

That whole first year was something of a daze, to be honest. I watched myself living in slow motion a lot of the time. I was performing comedy almost every night, in-between handing out flyers for the show and screaming at strangers in Times Square, followed by hanging out and drinking all night with other comedians and the occasional drunk audience member.

On the surface, I was getting by. But I was lost.

I wasn’t sure who I was anymore without my brother, and I was actively leading something of a double life, telling jokes and presenting a version of myself that didn’t represent at all what my life suddenly was. My whole worldview had been turned upside down, my ways of interacting with life fractured. I never talked about Russell on stage. My material was often kept to surface level jokes about smoking pot, drinking and thoughts on pop culture. I was desperately trying to hold on to a version of myself that no longer existed. And it wasn’t working.

I wasn’t sure who I was anymore without my brother, and I was actively leading something of a double life, telling jokes and presenting a version of myself that didn’t represent at all what my life suddenly was. My whole worldview had been turned upside down, my ways of interacting with life fractured. I never talked about Russell on stage. My material was often kept to surface level jokes about smoking pot, drinking and thoughts on pop culture. I was desperately trying to hold on to a version of myself that no longer existed. And it wasn’t working.

Offstage was no easier. Grief is so often swept under the rug, and we are encouraged to engage in it privately, if at all. Sibling loss, in particular, is one of the most under-acknowledged losses in my experience. We are often called “the forgotten mourners,” and for a good reason. There are more books about pet loss than sibling loss.

People seemed insensitive, almost dismissive to my grief, which was further isolating. The first question I often got when someone found out I’d lost my brother was often, “how’s your mother?” It was rarely followed up or paired with, “how are YOU?” People said I had to be strong for my parents. They just lost a child, it must be very hard for them.

Fortunately, I had the wherewithal to push back a little. I rarely let anyone off easy. I would often say, “Yes, I imagine they are doing about as badly as I am.” Friends were difficult to deal with, as well. Those who knew me before Russell died had a hard time dealing with the new version of me – a darker, more troubled version of myself.

My parents started attending a self-help support group called The Compassionate Friends. They encouraged me to come, as they had an active siblings group as well. I resisted for a while, but I ultimately went to a meeting, if only to shut them up. My feeling was, it wasn’t going to be helpful, and we’d never have to speak about it again. Ironically, all these years later, my parents no longer attend and I now run that same sibling support group.

This was really when things started to change for me. I had finally found a place where my feelings were validated, where my struggle was acknowledged, and my process was not judged. A place where I met other people going through a similar process who told stories of their own that I related to and where I was no longer alone. I could even joke about it in my group. Finding humor in the uncomfortableness of grief and death, in general, has been extremely cathartic. It has allowed me to talk about my grief and loss the same way that I talk about everything else.

It was when I started to embrace this new version of myself that I started to see real progress. When I let go of wanting to go back to being the person I had been, I was able to start getting to know this newer me. Not the old me. A new, still heartbroken version, who had found a way to go on.

In the intervening years, I started a podcast called Where’s The Grief? In which I interview comedians and other creative types who have also experienced a tragic loss (I often remark that it’s not ALL comedians, I do interview other sad people too). It felt like I had finally “come out” as a bereaved sibling, proud of finally being able to talk about my brother without making it weird.

And in doing so publicly, I started to see how much of a universal experience grief and loss can be. Showing all the different versions of what grief looks like and sharing those conversations with others in need, who are perhaps at an earlier stage of their journey has been very rewarding. To show other people that it’s okay to do it in whatever way works for you is also to re-affirm it for myself. Society, in general, does not deal with the extremes of grief well. Because there is no blueprint, I often thought I was doing it wrong.

People expect you to “go back to normal” at some point. People seem to think there’s a standard timeline for healing. They will ask when it’s clear you’re still struggling well past whatever that time frame is, “STILL? Aren’t you over that yet?” they say, “your brother wouldn’t want you feeling this way.”

Oh really? NO shit. What an incredible insight. What I wanted to say to all those who were disappointed in my grief process was that You think I WANT to feel this way? I don’t! But this IS how I feel. Also, Russell isn’t here, so he doesn’t get a say.

In the early days, grief was so hard, particularly because it was so unfamiliar. I was constantly blindsided by it. It would come out of nowhere. Standing in a supermarket staring at a carton of Apple and Eve apple juice. Hearing one of his songs (P. Diddy, “Bad Boy For Life”) blaring from a car radio. Even just passing a spot in the neighborhood that held the most mundane of childhood memories could be an emotional rollercoaster.

For me, one thing I’ve learned is that it’s only by acknowledging how I feel that I can DEAL with it. I have found that over time, just simply by doing that, the moments of intense grief pass much faster than had I repressed them or ignored them altogether.

There are still moments that come out of nowhere, but I’m much better equipped at managing them. The knowledge that dealing with Russell’s absence in my life is a lifetime process is a lot different than the scary thought in the early days of wondering when this pain would go away. Now I know. Loss does not go away.

There are still moments that come out of nowhere, but I’m much better equipped at managing them. The knowledge that dealing with Russell’s absence in my life is a lifetime process is a lot different than the scary thought in the early days of wondering when this pain would go away. Now I know. Loss does not go away.

I am now into my 20th year of grieving — not just for my brother and the life he didn’t get to lead, but for the life I knew as well. I lost a part of myself in the process, and while it took time, I feel like I have finally gotten to a place where I feel like myself again. By really allowing myself to feel all the feelings, to acknowledge my pain, and to incorporate this into my life, I have been able to accomplish this.

I will ALWAYS miss my brother, and I will ALWAYS wonder what he’d be doing if he were still here, what WE would be doing together. But as time has gone on, it’s not as scary or deeply distressing that it will never go away. It’s a reminder that my memories and my feelings about my brother will also never go away.

I will always strive to find ways to be more happy and grateful to have had Russell in my life in the first place than to be soul-crushingly depressed that I have to live the rest of my life without him. In a way, it’s a conscious choice I have made. I don’t always succeed, but the knowledge of the possibilities gives me hope for my future.

For more information about Jordon, you can check out his website.

Support us by driving awareness!

Subscribe to our YouTube channel at YouTube.com/GrapGrief.

Follow us on Facebook at Facebook.com/GrapGrief and on Instagram at Instagram.com/GrapGrief.