by Jamie Blanco

I don’t like the word closure.

It implies that some terrible experience or loss has been neatly addressed, packaged up and shipped out of your mind so that you can now function “normally” without excuse for emotional relapse. It assumes it’s a place at which you need to arrive, or else you’ve failed in some way. Or it is something that people expect you to attain so that they can be around you again without the burden of feeling the discomfort of the full range of human experience. It’s not polite to grieve. Grief is an ugly thing that, like most uncomfortable things, our society tries vehemently to ignore or hide away.

I disagree with that approach.

I think grief can be a beautifully painful journey without a destination and it is so important. I think embracing and expressing what you’ve been through and what you’re feeling is the only way to move forward and learn to live fully again. It’s also the only way to find the truth.

One truth I found in particular: Miracles are real.

I have witnessed miracles. And guess what? Miracles are messy.

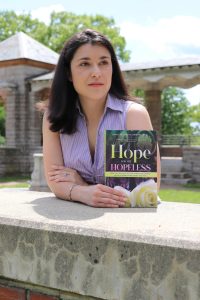

Here’s an excerpt from my book Hope for the Hopeless.

I was nine years old when my father got sick. We lived in a small, two-story townhouse in Miami, Florida, with a long backyard that backed up to a tollbooth behind the Florida Turnpike. We could see Florida International University and the National Hurricane Center across the highway from our covered terrace. The tollbooth bell sounded all day long from people blowing through it without paying, and the sound of ambulances whipping up and down the highway to the nearby hospital was constant. But it was always lush and green and warm outside.

My father built us a swing set, and at the very end of the yard, we grew bananas and mangos, though it seemed like hurricanes always blew the banana trees down every time they would finally give fruit. He tried to give us everything he never had growing up in the ’60s and ’70s on the streets of Bayonne, New Jersey, to poor immigrant parents.

I lived with my parents, my two younger brothers, my paternal grandparents, and my teenage uncle Lazaro. It was a messy, chaotic house full of love. It was the day before my mother’s birthday, October 26, 1995, and my father was going in for another long shift at Miami Children’s Hospital, where he worked as a respiratory therapist.

I sometimes wonder how many lives he would be saving today during the coronavirus pandemic had he lived this long. My father took as many double shifts as he could so that all three of his children could attend a safe private school. I remember being sad that I didn’t see him as much around that time because he was always at work.

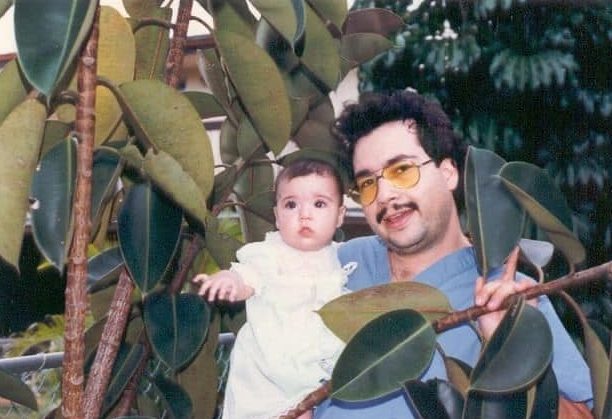

It was not because I missed him that nine-year-old me begged him to stay that night. I knew something terrible was going to happen. The feeling overwhelmed me. I cried for him not to go, to stay home and rest. I told him I had a bad feeling and that he shouldn’t leave. I pushed hard, but he said he had to go. He walked out the door in his blue scrubs, kissing me under his thick manicured mustache and huge, square ’90s glasses, shaking his thick, black, curly hair with an expression that said, “Don’t worry about me, kid.”

We woke up to the news that Daddin (our name for him) had been in a car accident and had to have surgery. Somehow, that didn’t scare me. I thought that since he made it to the hospital and the doctors were taking care of him, everything was going to be okay.

We woke up to the news that Daddin (our name for him) had been in a car accident and had to have surgery. Somehow, that didn’t scare me. I thought that since he made it to the hospital and the doctors were taking care of him, everything was going to be okay.

What I didn’t know was that he had suffered a massive grand mal seizure behind the wheel and he was undergoing life-saving surgery to remove a golf ball-sized tumor from his brain.

“I told you I had a bad feeling,” I told my mother. She and my grandmother whispered about it in Spanish.

At the time, my brothers and I went to a private Christian school called Tropical Christian School in the heart of horse country. It was one of the reasons my father worked so hard, so he could give his three kids, whom he loved more fiercely than life itself, a good education in a safe environment. Where we lived, in Southwest Miami-Dade near Eighth Street, was not exactly the best area for schools.

I remember my mother taking me to TCS and making me wait outside the office while she talked to the principal. I remember just being happy to get out of school for a few days, perfectly oblivious to the seismic tragedy beginning to unfold for my family.

There was a day I remember distinctly: The Friday after returning to class, we had a schoolwide church service, and the principal asked everyone to pray for my father who was in a car accident. My friends turned to me with looks of concern and confusion and asked, “Your father was in an accident?” And I just smiled and said, “Yup!” I wasn’t worried. I had no idea.

When we went to see him in the hospital, they had shaved his head and he had a huge half-moon scar on his head. He couldn’t walk, but he still joked with us and made us laugh, and we took silly pictures in the hospital room. I wasn’t worried. I had no idea.

A few weeks later, my father was home alone with us while my mother was at work. She was a medical transcriptionist at a nearby hospital. Daddin was still recovering and trying to sleep. My brothers and I were screaming and fighting when he got frustrated. He pulled us together and told us that he needed us to be quiet because Daddin was very sick.

And then he screamed at us (or it felt like screaming because he was crying and I’d never heard a more frightening sound in my life), “I have cancer!”

I don’t know what my brothers did; I vaguely remember them crying. J. J. was eight and Jason was six, so I don’t even know if they understood what it meant. But I did.

I remember calling my mother, who was at work and screaming at her, demanding to know why she didn’t tell me. Then I locked myself in my room.

I cried and prayed harder than I have in my entire life. I was in this state for at least an hour. I called up to God in my little voice and I begged Him not to take Daddin away from us. I begged Him to make me sick instead, to let us keep our Daddin. I had an almost out-of-body experience looking down on myself from the ceiling as I cried between my bed and the sliding glass window. I believe there was no small power in that prayer, and in all the other prayers from family, friends, and our school community.

Daddin was thirty-six years old, married with three young kids, and the doctors had just given him three months to live. But from day one he rejected the doctors’ death sentence for him.

He was walking with my mother in the mall trying to figure out what they were going to do when he stumbled upon a book called Sharks Don’t Get Cancer by Dr. William Lane. The book claimed that shark cartilage could slow or halt the growth of blood vessels that feed tumors.

He began taking BeneFin shark cartilage and other natural supplements, rejecting all traditional treatments at the time because they did not offer him hope for survival or quality of life. Because of his decision, doctors and surgeons refused to treat him. They told him not to talk to other cancer patients. He was turned down from several clinical trials because my father refused to stop taking his supplements. Nearly a year later, doctors wrote him off as having been misdiagnosed, so my father had his samples retested multiple times. They always came back the same: glioblastoma multiforme grade IV.

My father went on to educate himself about holistic healing and fought his disease on his own terms focusing on mind, body and soul.

He radically altered his diet to a far more healthful one, he utilized mental fortitude techniques like visualization (he pictured himself zapping the tumors with a laser gun) meditation and hypnosis. He also leaned heavily on his intense faith in God, declaring just weeks after his first surgery before our school church congregation, that God was going to heal him.

And healing did come. My father was given 17 weeks to live. He lived eight incredible years without mainstream medical treatment. No chemo, no radiation, no clinical trials.

Many doctors have called his survival a miracle. They’ve told me there’s no reason he should have been alive with the same aggressive and invasive tumor that claimed the lives of John McCain, Beau Biden and Ted Kennedy. And while on the macro level his survival was truly remarkable, living it day after day, watching his fight for life from home as a child, both the triumphs and the despair, was messy and traumatizing.

My father did not discover a cure but instead found a way to slow the progression of his disease. So, a tumor that normally recurs within a matter of weeks did not return again until three years later. He had another successful surgery and was healthy and tumor-free for another two years, then he had another surgery and another two years.

One of the side effects of surgery that he lived with was frequent and terrifying seizures, many of which he had while he was home alone with us kids. From that young age, I became my father’s caregiver when he would have these seizures, ensuring he would wake up from them, that he’d take his medicine, and that he was treated when he’d bite his tongue. I also took care of my scared little brothers.

And while I witnessed his tremendous tenacity and will to live, while I witnessed him defy the odds and far outpace his life expectancy, while miraculous, it was very hard on us.

I don’t only grieve the loss of my father, but the loss of my childhood and the emotional hardships that we all went through. And when he was gone, when the cancer did ultimately take his life in 2003 when I was 17 years old, I was left numb and directionless. In some ways, I felt like he had just moved to another hospital and was simply out of sight.

I don’t only grieve the loss of my father, but the loss of my childhood and the emotional hardships that we all went through. And when he was gone, when the cancer did ultimately take his life in 2003 when I was 17 years old, I was left numb and directionless. In some ways, I felt like he had just moved to another hospital and was simply out of sight.

I did not cry at the funeral to the chagrin of some family members. I felt nothing for a long time, focusing only on work and school and building my career and trying to reclaim my happiness and freedom. I buried myself in my love of nerdy things and found comfort there.

I felt a bit like a zombie. Something was switched off inside of me, but it didn’t mean I didn’t love him.

It wasn’t until many years later that I allowed myself to feel again. When I was safe and older and a mother myself that it all came back in high definition.

I rediscovered the book my father had written and relived it all through his words. I dedicated my life then to completing his work and telling both his story and mine. I allowed big grief to pull me down, I finally allowed tears to fall. I had at least two full-blown mental breakdowns while writing this book, but with the loving support of my husband and family, I was able to pick up and keep going until this project was done.

That’s how I grieved. Grief does not need to be a performative art nor is it linear. It is your internal journey and no one else’s and nothing to be ashamed of. As Vision states so succinctly in the show WandaVision, “What is grief, if not love persevering?”

We hurt because our love for that person remains. It should and will always remain. And through that love, we can accomplish incredible things that can help others just like us.

To wit, I have created a free cancer resource with useful information both holistic and mainstream, that can help anyone on their healing journey. Never be ashamed of your love. It’s not something you must complete, tuck away or forget. Once you’ve gone through the depths of that pain, you can find a comfortable place for that love to continue existing in your heart and mind.

I thank God for my messy miracle and I hope that my father’s story can help and inspire other families going through the hardest fight of their lives.

I love you. You will make it through.

For more information about Jamie, you can check out her website.

Support us by driving awareness!

Subscribe to our YouTube channel at YouTube.com/GrapGrief.

Follow us on Facebook at Facebook.com/GrapGrief and on Instagram at Instagram.com/GrapGrief.